Across the country, hundreds of books are being banned and/or challenged in school libraries and classrooms. Classroom favorites such as The Catcher in the Rye, The Color Purple, and Lord of the Flies are being pulled from shelves as parents, right-wing organizations and government officials complain that these literary works are too vulgar, anti-white, and sexually explicit to be read and taught in schools.

While the appropriateness for each of these banned and challenged books are debatable, the narrative that these books are harmful and shouldn’t be taught not only takes away meaningful lessons students should be learning, but it silences the voices of marginalized communities. It also threatens to exclude DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) in higher education.

For years, I, like many others, were assigned readings of books from the literary canon, most of which are written by and told from the perspective of a cis, straight white male. Canonical texts have long been seen as the standard when it comes to what’s important to teach as well as becoming staples in the steppingstones to creating better readers, exposing students to different perspectives and issues. However, it seems to have the opposite effect for students, especially for students of color.

After spending time in the classroom, both as a student and through the lens of a soon to be teacher, I see students struggle to engage and understand canonical texts. Many of them ask why they should care about something so outdated with little to no relevance to them or the world they live in. I found this to be especially true when trying to teach students the importance of Of Mice and Men. Most of them didn’t understand the text, even after careful explanation and using more modern analogies. Each lesson dragged along despite our best efforts to make the reading fun and relevant. However, when giving the students a more modern or relatable text, they were eager to engage with it, stating their opinions and getting creative with the text. Students were able to craft their own stories using poetry, create visual art, and, most importantly, see the bigger picture.

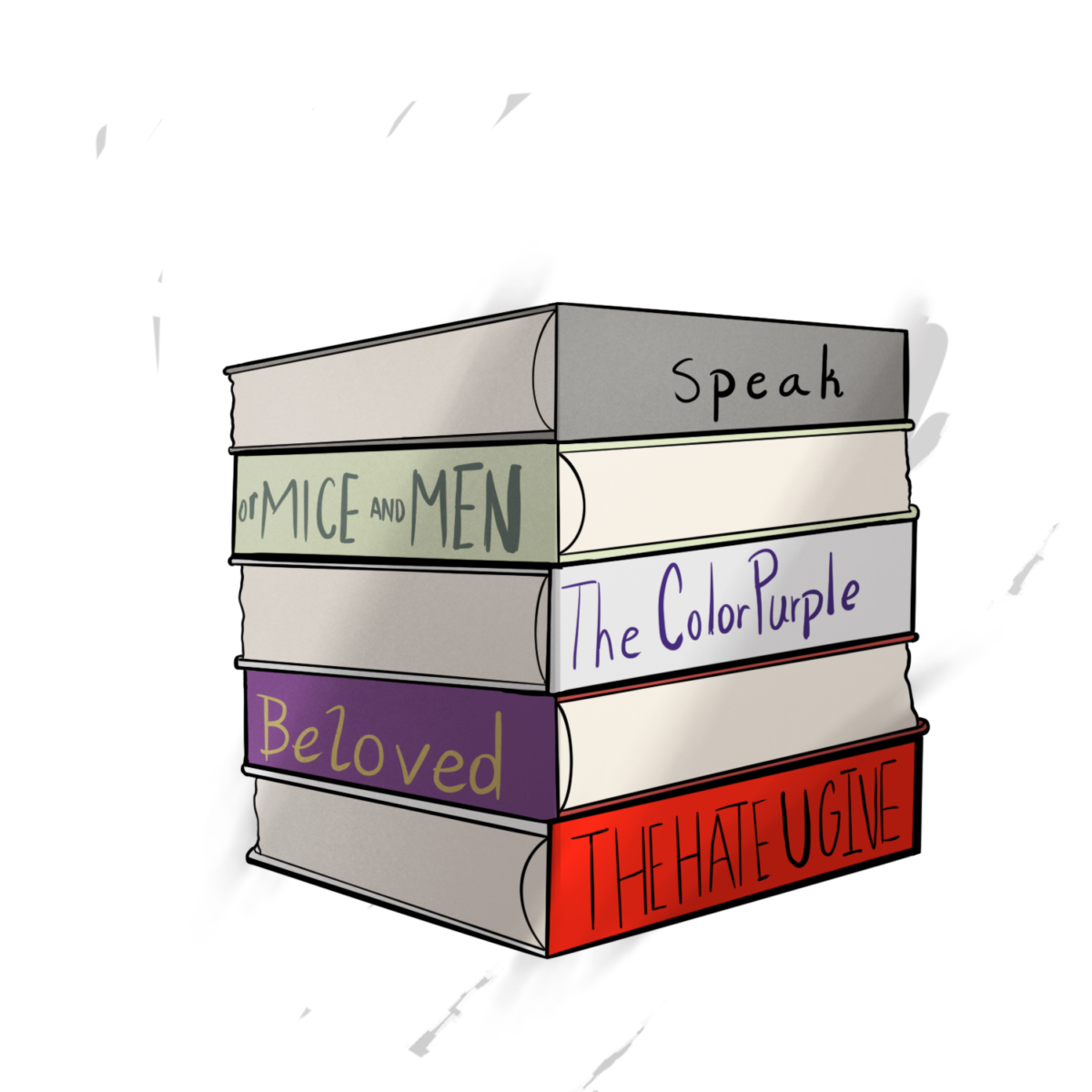

It has only been recently that modern literature has made its way into the curriculum with books like The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas and Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson, allowing students to be both culturally and socially aware as these books provide a more modern understanding of our society and those who live in it.

Modern literature allows students to see themselves in a form of media where they usually wouldn’t. It also allows them to gain important insight into the lives of people in other communities, gaining an understanding of experiences outside of their own. These texts teach students important lessons like consent in Speak; racial bias in The Hate U Give; the intersectionality of race and sexuality in Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe; and the dangers of ignoring signs of abuse in Monday’s Not Coming. Including modern literature in the classroom is a big step in creating a more empathetic society as students can relate to these books and apply them in the real world. It should be something to celebrate.

“It’s very important for students to see themselves represented in the classroom,” Professor Jenna Bates said. Bates is an adjunct English professor at Kent State University. “If we only ever read dead European white guys, then there’s a whole population that isn’t getting represented. As a teacher, that’s my primary concern.”

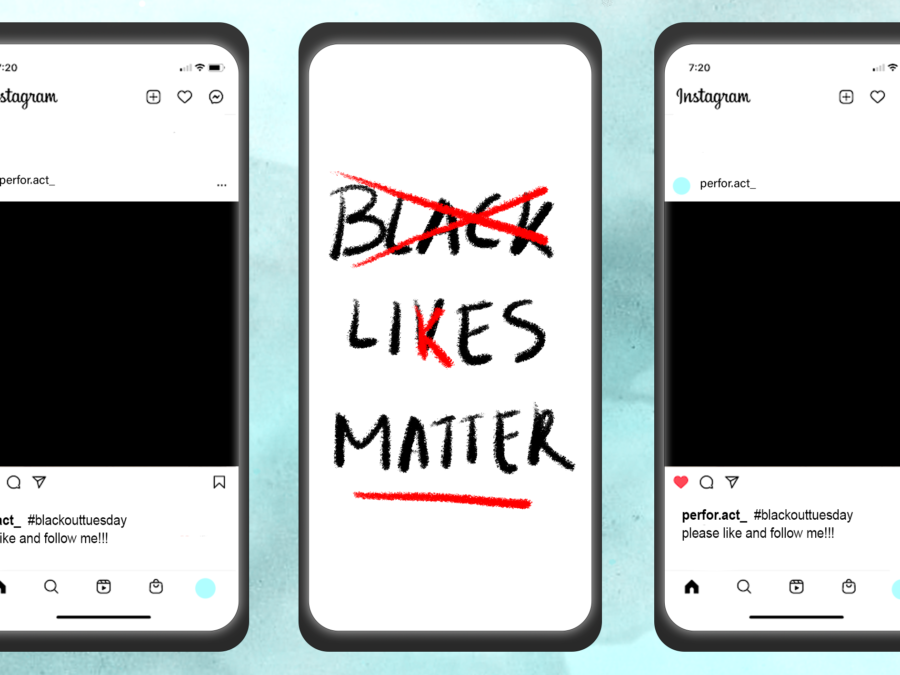

Unfortunately, many people disagree. However, their disagreement is nothing new when looking at the involvement of African American literature in the curriculum that have been taught in past years.

In 1997, one of Toni Morrison’s most popular books, Beloved, was challenged at St. Johns County Schools because the language was too vulgar. In 2007, parents of students at Eastern High School in Louisville, Kentucky had the book pulled from an AP English class because the novel “depicted inappropriate topics of bestiality, racism, and sex.”

Complaints like this not only affect students’ learning opportunities in secondary education, but those in university and college.

Earlier this year, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, signed SB 266 which will stop public colleges and universities in Florida from using federal funding for majors, courses, and programs that fall under DEI and CRT (Critical Race Theory). With the passing of this bill, it will only be a matter of time before other red states across the country follow suit.

In May of this year, the Ohio Senate passed SB83, the Ohio Higher Education Enhancement Act which will be mandatory diversity training and teachers will be evaluated on how biased their classrooms are.

Sen. Jerry Cirino, who introduced the bill, stated that this bill is for those who want an education that tells both sides of the story without being told what they should believe.

“This legislation is an urgently needed course correction. If you desire an education that involves learning analytic skills, evaluating many ideas and many sides of issues and how to think better, not what to think, this bill is for you.” However, higher education isn’t only about evaluating the many sides of an issue. It’s also about how we can solve them and what or who is stopping us from doing so.

It brings into question: who will be at these universities and how will it affect teachers?

“If you’re telling people they can’t major in certain things or they can’t take certain courses, and then in turn, they can’t teach those,” Bates said, “you’re not going to have people at your universities and an even worse teacher shortage both below at the post-secondary level…it’s a sad state for democracy when we are being told that we no longer have intellectual freedom in what we teach and what students learn.”

Teachers and students alike will be affected by the book ban personally and professionally, but what are these parents and organizations afraid of? What is so vulgar or inappropriate about the lives and experiences of marginalized communities? It’s possible they’re afraid that their children will learn about the history of this country and how their race may or may not have been affected by it. Or how gender norms don’t determine who they are or who they feel attracted to. Controlling what their children read is the only way they can guarantee that their beliefs and ideas of normality stay the same from generation to generation, and another way to make sure marginalized communities don’t receive the empathy or reparations they deserve because it might mean facing their guilt and admitting their privileges.