Article by Alex Gray and Lyndsey Brennan

E. Timothy Moore, associate dean emeritus in Kent State’s College of Arts and Sciences and emeritus professor of Pan-African Studies, died unexpectedly on Feb. 1 from an aortic dissection, a tear in the major artery coming out of his heart. He was 69.

He is survived by his wife of 47 years, Debra “DeLacy” Moore; his children, Elliot Moore and Candace Garton-Mullen; his mother, Iris Moore; and his brother James Moore. He was preceded in death by his father, James “Fronts” Moore, and sister, Gayle Moore.

During the five decades Moore spent on campus as a student, professor and dean, he advocated for students of color and pushed for policies and programs that would make Kent State a more welcoming, racially equitable campus.

“He was like our John Lewis, seriously,” said Gene Shelton, a classmate of Moore’s who later became his colleague as a journalism professor at Kent State. “A young man who knew early on what he had to do and how he was going to do it.”

People knew him for his calm and inviting demeanor that enabled him to connect with, support and empower colleagues and students from all backgrounds.

“The overall energy that my father brought to the room was just really wonderful, and it’s really, really missed,” said Garton-Mullen, Moore’s daughter.

On the KSU Black Alumni Facebook page and Moore’s personal page, faculty, alumni and staff left over 200 messages recounting memories and stories of how Moore changed their lives for the better. The outpouring of love for her father left her with mixed emotions, Garton-Mullen said.

“It’s also been really hard because it’s like, my dad is gone, and all these people talking about how great he was [is] just a reminder that he’s not here,” she said.

Much like the powerful artwork he left on campus, his work with the university and its alumni has staying power and will shape the course of the school for decades to come.

“He didn’t limit his love”

When Moore came to campus on an art scholarship in 1969, he was swept into the flurry of activity generated by Black United Students (BUS), which brought big names like Nikki Giovanni, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder and Gwendolyn Brooks to campus and originated events like the Renaissance Ball and the Pan-African Festival.

A walkout initiated by the members of BUS happened the year before Moore arrived. In the wake of their activism, the Institute for African American Affairs (IAAA) and the Center of Pan-African Culture were established.

Moore got involved right away, joining Omega Psi Phi, a historically African American fraternity, as a freshman, singing in the Black Ensemble as a sophomore and becoming president of BUS as a junior.

Silas Ashley, Moore’s classmate and friend of 52 years, said Moore was elected president of BUS because of his “calming spirit,” and under his leadership, membership increased dramatically. Moore’s even temperament helped smooth over disagreements in the community, a practice he carried into his work as an administrator.

“He wanted to get things done, and he did, but he always kept that even keel. You could not fluster him,” Ashley said.

“Even as a freshman, he stood out,” Shelton said. “He was tall. He wore his colors proud, but he didn’t limit his love and respect to his fraternity brothers. He extended it to everybody, and I think that’s what made him such a great leader.”

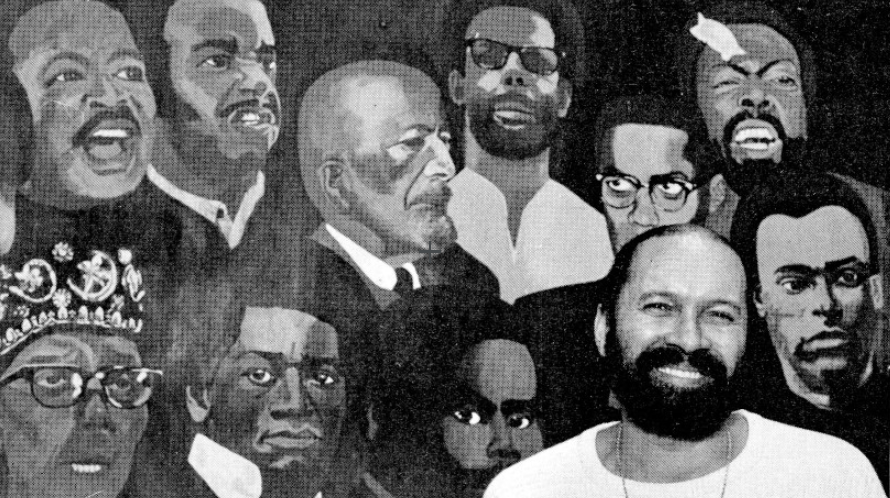

Moore left his literal mark on campus in 1973, when IAAA director Edward Crosby invited him, along with two other students, to paint murals on the walls of Oscar Ritchie Hall. (Crosby also died this month on Feb. 10. He was 88 years old.)

Crosby wanted students — many of whom came of age at the peak of the civil rights movement and were grappling with questions about their own Black identity — to see themselves and their culture reflected back to them as they walked to class.

Pat Burk/The Daily Kent Stater.

Moore chose to surround his fellow students with portraits of some of the country’s most celebrated Black thinkers, orators and writers. Alongside big names like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Frederick Douglass, he included figures students may have recognized from their visits to Kent State: Amiri Baraka, Jesse Jackson, Muhammad Ali and Stokely Carmichael (who later became Kwame Ture).

“A window into our history and heritage”

After graduating with his bachelor’s in fine arts in 1973, Moore remained at Kent State as an instructor while completing his Master of Arts in 1977 and his Master of Fine Arts in 1983. All three degrees were in visual communication design.

“One thing that has kept me here after I graduated is the atmosphere,” Moore said in a 1989 article in The Daily Kent Stater. He especially loved mingling with students and watching them interact in Oscar Ritchie Hall, the hub of academic life for Pan-African Studies students, which he said made him “feel as if we’re carrying on the tradition” his classmates had started.

As an instructor in the Pan-African Studies program, he created courses such as Introduction to African Arts, Aesthetics & the Black Community and Communication as an Art. For over two decades, he served as the faculty adviser to UHURU magazine and Black Watch newspaper.

“Tim was able to share the Black experience in such a way that it brought people into it,” said Mwatabu Okantah, a professor of Pan-African Studies and director of the Center of Pan-African Culture at Kent State, who was also an undergraduate classmate of Moore’saps.

“For Black and non-Black students, he provided a window into our history and our heritage,” Okantah said. “That content can be difficult for students because they respond to it on a personal level, but Tim was adept at helping them navigate through it.”

Moore’s teaching helped shape many students in and out of the Pan-African Studies department. For Carletta Fellows, who transferred from a historically black college and graduated from Kent State in 1993, Moore’s classes provided her with insight she had never experienced before in a classroom setting.

“Although I went to majority schools of color, [with] Black people specifically, this was the first time I was really introduced to figures in literature by African Americans that I was not familiar with,” Fellows said.

“It allowed me to further my knowledge by getting more books, and [Moore] encouraged that. He encouraged me to really kind of grow in our studies, even if that was not our major.”

Moore was a meticulous researcher who modeled to his students how to verify facts with academic evidence. This became clear when Moore researched the origins of Black History Month. After six months of sifting through archival information, he found that Milton Wilson, a dean, had marked Black History Month on an official school calendar from 1970.

“Up until that point, it was just legend and hearsay,” Ashley said, “but he took the time to sit down and verify it, so that it would be without question.”

“Just being in his presence, you felt better”

In 1998, Moore became an assistant dean in the College of Arts & Sciences and two years later was promoted to associate dean, a position he held until he retired in 2010. Among his duties as dean, Moore spearheaded multicultural initiatives, moderated discussions about race relations on campus and pressed administrators to implement a university-wide diversity curriculum.

“Any effort that moves us toward interaction between the diverse groups is favorable. The more we interact, the more we understand one another,” Moore said in a 1994 article about the university’s diversity programming calendar.

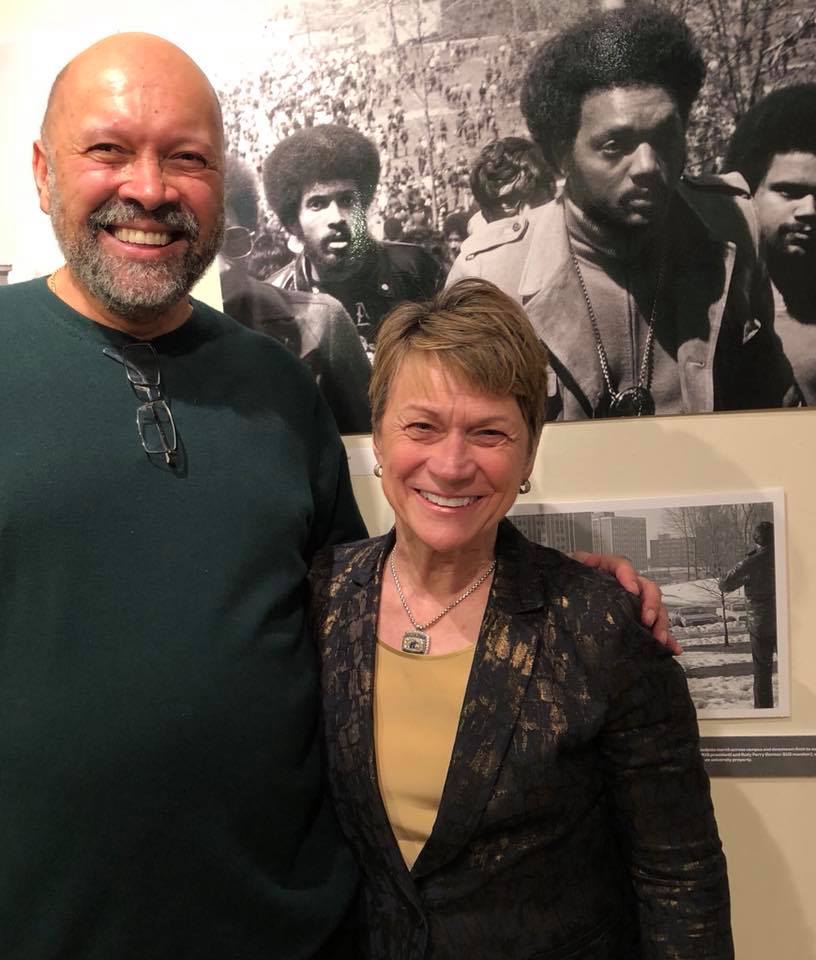

Photo courtesy of the Moore family.

“Tim’s outlook on life was that we’re not here at Kent to be separate entities. He wanted to show the community we could interact, cooperate and work together to make the whole university better,” Ashley said.

Kent State acknowledged the contribution Moore made in this area by awarding him the Diversity Trailblazer Award in 2015. Moore received a number of other accolades, including the Distinguished Teaching Award and the E. Timothy Moore Outstanding Faculty/Staff Award, a recognition BUS established in his name in 2011.

Moore was a skilled adviser who had a knack for making students comfortable enough to share a problem so he could help them solve it. “Tim was always that person. If a student was depressed or angry, he had the kind of demeanor where, just being in his presence, you felt better,” Okantah said.

“Now don’t get me wrong: if the situation called for a student to be chastised, he had to tell them, ‘No, this is the rule here.’” Ashley said. “But he could do it in such a way that the person leaving wasn’t bitter.”

Moore never demanded respect from students, Shelton said, but after spending time in his presence, “You had no choice — you wanted to respect this man. A moment in his presence was a period and moment of growth for you. And even I felt that.”

Crosby, who served as a mentor to Moore, taught students that the true measure of a Black institution is its ability to outlive its founders, so we owe it to Moore to “continue to do the work that he was engaged in,” Okantah said. “If the larger community values his memory, it will value the institution he helped create and sustain.”

Shelton agreed. “As long as we keep the work, the effort, the actions, and the words of Tim Moore alive — even though he has left us — we will never lose him,” he said.

Moore’s family encourages colleagues and alumni to leave tributes to Moore on a memorial website created in his honor. In lieu of flowers or gifts, the Moore family asks that memorial contributions be made to Susie’s Wagon or the E. Timothy Moore Scholarship Fund.

A celebration of his life will be held virtually over Zoom on Feb. 25 at 8:30 p.m. Participants will have opportunities to speak on Moore’s impact and legacy during dedicated breakout sessions. A collage of photos of Moore depicting his life from childhood to the present will be displayed throughout the program.

Attendees are required to pre-register here.

Contact Lyndsey Brennan at [email protected].

Contact Alex Gray at [email protected].